The Rich and Turbulent Tapestry of Guadeloupe: From Arawak Roots to Contemporary Reflections

Arawak Origins and Carib Arrival

Long before European explorers set foot on its shores, Guadeloupe was inhabited by the Arawak people, known for their peaceful, agricultural society. Their artistry in pottery and structured social systems set the stage for the island’s first cultures. In the 15th century, however, the Caribs, seafaring people known for their warrior traditions, arrived from South America. Gradually, they displaced the Arawaks, leaving a cultural footprint that remains visible in Guadeloupe’s place names and traditions.

European Colonization: The Struggle for Control

Christopher Columbus first sighted Guadeloupe in 1493 during his second voyage to the New World. Despite Spain’s initial claim, it was France, under the leadership of Charles Liénard de l’Olive and Jean Duplessis d’Ossonville, that began to establish a permanent settlement on the island in 1635. Thus, Guadeloupe found itself ensnared in the intense struggle between European powers vying for colonial influence and control in the Caribbean. The island’s colonial narrative is a web of treaties, invasions, and power shifts, particularly between French and British forces.

The Brutal Era of Slavery and the Sugar Economy

To fuel the burgeoning sugar cane industry, European colonizers turned to the mass importation of enslaved Africans. Guadeloupe became a prominent, dark nexus in the trans-Atlantic slave trade. Enslaved Africans suffered brutal conditions while they sustained plantations that yielded immense wealth for European elites. In 1848, after tireless advocacy by Victor Schœlcher, a French politician and staunch abolitionist, and following widespread resistance by the enslaved population, slavery was finally abolished in Guadeloupe.

Political Turmoil and the Geopolitics of World Wars

Throughout the 18th and 19th centuries, Guadeloupe was a prized possession that changed hands several times between French and British powers. Its geopolitical significance was further highlighted during the World Wars. In World War II, Guadeloupe initially aligned with Vichy France, reflecting the fractured politics of the French empire, but later joined the Free French Forces under Charles de Gaulle.

The Path to Departmentalization: A Double-Edged Sword

In 1946, a significant political shift occurred when Guadeloupe officially became an overseas department of France. This departmentalization granted the inhabitants French citizenship and aimed to more deeply integrate Guadeloupe into the French state. While this status brought notable benefits, including access to social welfare and healthcare systems akin to those in mainland France, it also catalyzed significant political and social tension. Contemporary debates about autonomy, identity, and the impacts of assimilation policies frequently dominate the island’s political discourse.

Contemporary Reflections: Reckoning with a Complex Past

Today, Guadeloupe is not just a picturesque Caribbean paradise; it is an island deeply engaged with its complex history. The Mémorial ACTe museum in Pointe-à-Pitre stands as a solemn and impactful tribute to the memory of slavery and the slave trade. Designed with architectural elements that symbolize the island’s historical ties to slavery and the sugar industry, the museum is not only a repository of information but a poignant narrative tool.

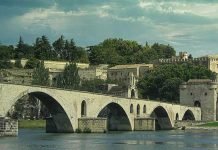

Beyond the museum, Guadeloupe’s landscape is dotted with the ruins of sugar mills and plantations, forts, and colonial-era buildings. These sites are not mere relics; they are living memorials that bear silent witness to the trials, tribulations, and resilience of the people of Guadeloupe.

For the sophisticated traveler, engagement with these sites offers more than a history lesson. It provides a profound connection to the island’s past that enriches understanding of its vibrant, multifaceted present-day culture and society. Through this lens, Guadeloupe is revealed as a place where beauty and pain, past and present, are inextricably intertwined—a rich, complex tapestry that continues to evolve.